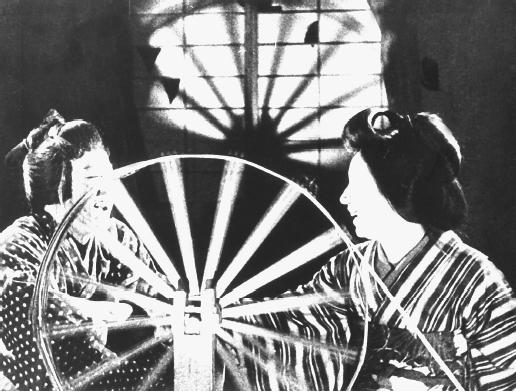

Crossroads (1928) (d. Kinugasa Teinosuke)

Spring on an Island (1940) (d. Toyoda Shiro)

Quick impressions on two films. Older Japanese works startling in their use of male subjectivity as site of confrontation with nationhood and modernity. Usually, it’s the female consciousness and body that’s at stake. Up first is Crossroads (Jujiro) by the auteur behind Page of Madness. It’s a bit overlong when it comes to the sentimentalized modesty of the sister’s sexuality: will she sell her body for her brother’s many mistakes? The film is at its best when the protagonist has to confront the actual unmodest sexuality of the times: as he is blinded he can also see more clearly through the jeers of his geisha lover, rivals, and society at large. The geisha is called Onume where “me” is eye for Japanese. The climax returns the Odysseus/Oedipus figure to the pleasure grounds only for him to have a heart attack because he can no longer face what Japan has become (and if you look at date of production, 1928, where the country has been and where it’s headed). He expires because he chooses his sister, where nostalgia and attachment to past is figured as unapologetically incestuous, unproductive (spin wheel as old technology), and unrealistic. He literally falls apart in front of us. Death could not come sooner to rescue him from incredible depths of madness. Kinugasa places the camera up above the fallen man as spectacle for visions of what other men will have to face in the next few years. The film ends with the eponymous crossroads when we all know very well and audiences back then surely knew it too which road the country would take, disastrously.

The next film is smaller and staid by comparison by a director I’ve never heard before named Shiro Toyoda. The film is called Kojima no Haru (Spring on an Island) made in 1940. Essentially, film is about a Japan that is disappearing by focusing on life and illness in a small island. The narrative is slightly confusing because it doesn’t clearly delineate from the start that the actual protagonist is a female doctor, and in fact that’s why the film works because the figure of modernity is a woman whose profession, clothes, and commitment marks her as the Japan that should be aspired to. The film is also not really about physical illness. The illness could also be those left behind by the nationalization project, those in the boonies. Those rounded up are read as potential lepers but it’s possible to read them as those who are too old-fashioned for where Japan is headed. For instance, the key melodramatic figure is the father who is ill but refuses to leave the island. Upon first encounter, he doesn’t look like a patriarch as much as an intellectual, an agitator, or even a dandy because of his tinted glasses. The simplicity of his clothes doesn’t translate to countryside humility but almost a deliberate, chic minimalism. It’s when he’s forced to leave the island that his un-modernity becomes apparent. He’s suddenly wearing a male kimono when there are no other males in the sequence wearing this old fashioned garb. The male doctor signals European training while the town officials although dowdy aren’t stuck in the past. It’s the father’s resigned stance that makes him the unwonted figure of modernization. (Or his type of modernization, the leftist intellectual or the anti-war activist, the kind that need to be cured.) The one who weeps the most is his son while the female doctor, although on the verge of tears, checks her emotions beneath a stylish hat. I didn’t know when the film was made when I saw it and thought post-war but the ending seemed very odd because the movie couldn’t quite end naturally. Look, the guy is finally on the ship, with the doctor protagonist, and the kid is weeping across the way. But shot after shot the movie doesn’t let the boat land on the other side. Why is this? Had the boat landed we can imagine a potential cure for the dad and his eventual return, but the movie can’t commit to this simple ending and in fact doesn’t let the boat land. It was upon finding out that the movie was made in 1940 that it all made sense: the project of nationalization and modernization didn’t end well. Or that the ghost ship is still cruising towards a better destination. Timely movies, these turn out to be.

#2017