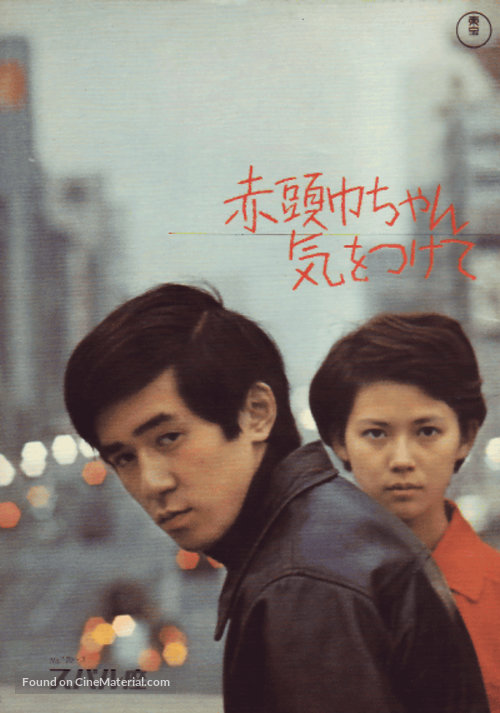

Take Care, Red Riding Hood (d. Moritani Shiro)

It doesn’t know what it wants to be and it’s not a good movie. Released in 1969, the film follows a college bound student whose plans to begin his studies at Tokyo U is derailed by student protests. The film is so annoyingly classist that it thinks not going to Todai is gonna be the end of the world. It’s also terribly sexist as the women around the young man, including a young child who wants to get an age-appropriate Red Riding Hood book, are there only to explore aspects of his not quite convincing angsts. Even the female doctor is stripped naked for his fantasies, the doctor being the only professionally accomplished woman in the film. A neighboring housewife is insultingly given a bird sound effect because of her endless prattle and because of her attempt at chicness, a feathered hat. We instead get a long, dragged out conversation between the protagonist and his male pal about LIFE. It’s such a bore fest. There are musical interludes for record single releases, I suppose, and a low-key orgy that segues into a jazz song. As I said, the movie doesn’t know what it wants to be. The general tone is that of innocence when it should have been acerbic. The film ends with newsreel footages of student riots, American military presence in Japan, and stylized black and white photographs of nude westerners with just a suggestion of both interracial and homosexual couplings. These things don’t cohere and they seemed tacked on. Released by Toho, why did the filmmakers bother to throw in these images? As a response to independent films, filmmakers, and ATG who were tackling some of the same topics? For me, this undecidability is a sign of optimism. The protagonist decides at the end that he will quit not go to school and make it on his own, which means that he could imagine an alternative from the clutches of school-work-death pipeline of Japanese society at that time. While his girlfriend tries to make out the Tokyo neon signs at night and admires them, he seems nonchalant at the spectacle afforded by the restaurant. He is not to be tempted. He will not stick with the system and the film says that’s OK. It’s something that cannot be said openly these days in an economically uncertain Japan. In this way, this mediocre film achieves a thimbleful of radicalism—for upper middle class Japanese men.

#2019 #112