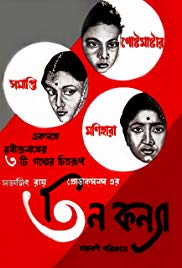

Three Daughters (d. Satyajit Ray) (1961)

From 2014.

Originally conceived as a three-part film, with each story running roughly an hour long, Ray explores the fates of women in Indian society of the 50s. The middle film, the part that had been missing for decades, involves a ghost story in a once opulent mansion conceived in the manner of an English country estate. The film itself is a phantom as the film was released internationally without this section. The haunting presence or absence (since it is the thing that is not explicitly dealt with) is the issue of British imperialism and colonization. The wife’s obsession is non-sensical since the camera is concerned with the space, furniture, and ornaments of the English-style estate. (The characters in the film are ‘ornaments’ themselves as ornaments /jewelry is the key word here.) The ghost that lurks the mansion and garden outside is the influence of British values and ideas in a colonized country. What Ray brilliantly shows (by accident, I feel) is how the colonized subjects, the educated middle and upper classes, become curious actors in their own land, confused and unable to make the right decisions with regards to those unlike them: those who don’t speak English and have no British sensibilities. This is why the male character in the first section is unable to do the sentimental or right thing by mainstream movie standards. And this is why the male character in the second (third in the original conception) essentially tames his wild woman with a sentimental gesture.

On the primary level, the film uses the fate of women to show the state of Indian society of the period. These women are not Mother India (an iconic film) but instead are daughters of hers, which might explain the title. In addition, the daughter designation also frees them from the responsibility of representing the Nation; and they are of age to marry and create families of their own. But no families are created in these domestic stories. The women’s tears are epic, as Ray is able to bring out amazing performances from his actors, but the stories themselves seem to be in a tradition of (what I can only describe as an) old-fashioned humanism.

There is something intact about the characters, solid, recognizable as some kind of lower-case archetypes. They way they react to the world is in accordance to a strictly defined psychology which doesn’t waver except for the woman in the ghost story whose motivation is unstable and hence her unresolvable absence/presence which then indicates what constitutes a viable character, the one who can be read as a recognizable figure. What is of interest is the woman in the second film, the section that never got released, because her character cannot be contained and could not be sustained as a viable presence. Her state shows Ray grappling with how to portray a character of differing motivations or it shows Ray’s awareness of his own limitations because the world around him could not provide him with the vocabulary to do so.

The form of the short story itself appears to be part of this idea of humanism, in the belief that things can be conveyed in this form which Ray transmutes into the medium of film. These stories are ultimately unreconcilable, which explains the state of the film for so long with the missing middle section, because it follows the stories rigorously from its original form which in turn brings its attendant ideas about characterization and what makes one a human being. This may explain the presence of strange humans and animals in the narratives: a crazy old man, a pet squirrel, and a mysterious cousin. These are figures that never made it to becoming characters–rather they appear as ornaments in the films.

More significantly, there are the British accessories–a book by Scott or Tennyson, portraits of the royal family, western jacket, to name a few that function as signs of civilization–as the film itself tries to be. I’ve never been convinced of Ray’s work entirely (except for the poetic Pather Panchali), not sure to whose eyes these films were made for. The dismembered fate of the film reveals how colonialism has yet to be reconciled in Ray’s consciousness; and the current reincarnation of the film–the third film was screened separately–shows that the non-diegetic world of the film has yet to confront its colonial past.

#2014 #July