Balikbayan Box #1—Memories of Overdevelopment Redux #4 (d. Kidlat Tahimik)

With a title like that, I should have known how self-indulgent, long-winded, and self-important the work, cobbled together from three working films, was going to be. (The film has a 2 hour 40 minute running time.) Tahimik is the OG of Philippine indie cinema, but like some OGs, their sensibilities can be stuck in the past and their current work are just riffs and elaborations of a kind of thinking that is archaic to contemporary audiences—but exotic enough for foreign viewers.

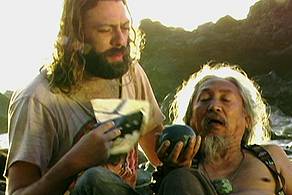

His name already tells you that a) it’s a pseudonym (kidlat = lightning and tahimik = silent, thus silent lightning) and b) it’s a self-orientalizing ethnicized/indigined persona running against the grain of American and European perceptions of the Filipino and the Philippines but also playing into it too. It’s a persona that was popular in the 70s, a mixture of western hippie-ism and nationalist fervor for anything indigenous of Philippine origin, which explains the mash of regional indigenous identities paraded in the screen and the needless native loincloth appearance. He wants to be a Filipino folk figure but he comes across as its unintentional parody too. Take a look at the film itself.

For a film about the Philippine past, it is populated by many white people. In fact, the narrative is driven by a white man’s search for him. The white man (played by the director’s son), who seems to have been in the country for a long while, speaks in a Filipino English accent unlike the director who speaks with an American one. Ditto the other white people who are in the film. Their English is inflected with Filipino accents while some of the Filipinos in the film speak with an American one. Why does the film have to center on a white protagonist? I think that Tahimik is still working under the presumption that white presence and white accent legitimizes the film even if he keeps on insisting with his words and appearance that he is looking for the native version of history. There’s also the strange relationship with the other man signified as native. They speak English with each other most of the time, never occurring to them how odd this form of communication is. (I thought it was because the other man couldn’t speak Filipino and could only speak English and a dialect, but later they do speak Filipino. They must be of the generation where English was generated as a sign of civilization even if they speak it so dressed in native costumes.)

Tangent. There’s a witty sequence in the Filipino American indie movie Bitter Melon that highlights the unique verbosity and vocabulary of Filipino English. The uncle, probably the same age as Tahimik, keeps talking in this odd English while the next generation kids can’t suppress their laughter. I’m only bringing this up because in the final segment of the Tahimik film, he directly addresses the camera and comes up with what he thinks are witticisms in English, but comes across as a dated form of Filipino English, like the uncle’s in Bitter Melon. And it’s not just language, his conception of the world is similarly dated, too. Not once is the term post colonial mentioned even if that is what he’s trying to do, with mixed success, in my opinion.

There’s also something objectionable about his indigenous-ness. It’s an act, a cultural one. There’s no actual political or economic analysis in his account even if he see him participating in a strike. It seems that strike itself would have been a far more interesting and enlightening subject matter than what he does in this work, which is basically revisiting and extending his past themes. There’s no mention of Marcos. There’s no mention of the current economic state of the country despite having the term overdeveloped in the title. What matters to him is this imaginary figure of a Filipino slave/stowaway who ends up circumnavigating the globe with Magellan as if that is an effective counterpoint to Spanish and American colonialisms. How so? the film never makes it clear. Although he make sure that we note that Tahimik as the slave beds a white woman, on and off screen, a kind of racialized machismo that really dated the director’s thinking.

Ironically, it’s the credit sequence, a parody of karaoke sing a long with running text about Magellan’s death in Cebu that perfectly encapsulates the themes of the movie in a succinct, humorous, and post-colonial manner. Had Kidlat just shown that, I’d given him an Oscar.

#2019 #40